Pao Ramen

-

RSS Search

Jan 29 ⎯ Very interesting feed aggregator. You can search any term and it returns results from all the feeds they have indexed. The searches themselves are also RSS feeds, so you can subscribe to “topics”. Perhaps I should integrate this to fika to help people discover new feeds? Once I do tag and topic extraction, we could automate this to add a bit of entropy and kickstart the recommendation flywheel.

-

Coding without planning

Jan 29 ⎯ Another example of plan to start vs plan to finish. Like writing, or playing music, there are different characteristics to a planned strategy to an improvised one. As one gets more experienced, intuition based approaches tens to have better outcomes than rational ones.

-

Deepseek and the Jevons Paradox

Jan 28 ⎯ Nvidia is down 17%. Deepseek has released their latest R1 model which they claimed to be trained very cheaply. Half the internet is calling it a bubble burst, the other half are rushing to buy the dip. Who is correct? Well, that's not so easy. What would Charlie do? At this point, it's not about the fundamentals anymore. It's just to speculate about AI and the role of Nvidia. One thing is clear, though: efficiency gains in tech tend to increase consumption. Let's see if AI also follows the Jevons Paradox.

-

IP query

Jan 28 ⎯ Interesting service to query anything about a given IP. I’ve had to implement this at every single company, mostly for marketing reasons. This service seems to be free, so it’s a good bookmark to have around.

-

Building on top of ATProto

Jan 28 ⎯ An exploration about building a side-project app on top of ATProto. I’m saving this since at some point, I want to integrate fika with Bluesky. I enjoy a lot the “captain-log” kind of articles. It’s always interesting to see how people build and learn. As usual, it’s also comforting to see people sharing the same struggles: As always, the hardest part of this project, as with any project, was understanding the data model and the business logic, and parsing out those objects correctly. The second-hardest was aligning elements in CSS.

-

Like Scratch, but textual!

Jan 28 ⎯ Very interesting project to teach programming to kids. The main difference with Scratch is that Hedy uses Python (yuck!) on a textual environment. To be able to reach kids around the world, they’ve open sourced a python-like language that is multi-lingual. There is of course the eternal debate to whether kids should learn to program or not, exacerbated by the advances in generative AI. But I still think it’s a valuable skill, the same as calculators didn’t deprecate mathematics. I would even go as far as to claim that it probably should displace some of the maths, since it’s clear by now, that the Newtonian way of describing the world through formulas is perhaps not the best one. Perhaps Wolfram’s point of view, that nature is perhaps better described through programs, is one worth exploring. I will definitely give it a try!

-

How Substack Is Remarkably Changing The Game For Good

Sep 23 ⎯ www.productreleasenotes.com

-

General agents contain world models

Sep 22 ⎯ share.google

-

Entri | APIs for Domains

Sep 22 ⎯ www.entri.com

-

Blog | OH no Type Company

Sep 21 ⎯ ohnotype.co

-

AI Will Not Make You Rich

Sep 21 ⎯ joincolossus.com

-

Ongoing Tradeoffs, and Incidents as Landmarks

Sep 21 ⎯ ferd.ca

-

A UX case study of Markdown heading

Sep 20 ⎯ share.google

-

Cluely Thesis on Virality and Hype

Sep 20 ⎯ cluely.com

-

Web Interface Guidelines

Sep 20 ⎯ vercel.com

-

Dither Plugin

Sep 20 ⎯ dither.floriankiem.com

-

Run & Relax

Sep 20 ⎯ fika.bar

-

Your Review: Project Xanadu - The Internet That Might Have Been

Sep 19 ⎯ www.astralcodexten.com

-

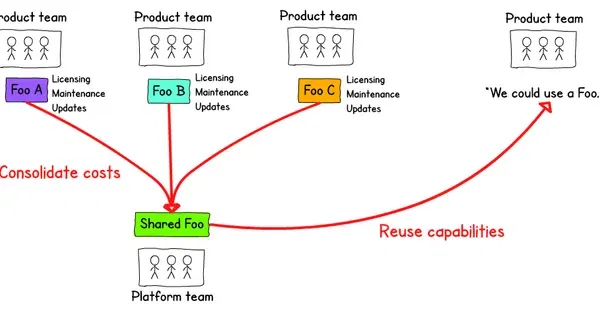

Platform teams: the eternal debate

Jan 27 ⎯ As a CTO, one of the unsolved challenges is whether to have a platform team or not. This article explores the downside of building platform teams. I think the article is a little bit biased and presents only one way of implementing platform teams. I still believe that platform teams are a net-positive, but only when they use golden paths to achieve their goals.

-

Web Monetization

Jan 27 ⎯ A web3 way of accepting payments on the internet. Looks pretty cool, and could be a good way to counter the SaaS models of medium and substack. As usual, though, the challenge would be for adoption to go mainstream.

-

Doc Publication

Jan 27 ⎯ There is a revival of publications. Individuals join and curate and write content. And you, instead of letting an algorithm determine what you read, subscribe to those publications. In this case, the people of UX collective decide to own their own publication and monetize it with Web Monetization, a web3 way to accept micropayments. I hope fika allows people to create such beautiful publications.

-

A list of long-form articles worth reading

Jan 27 ⎯ When I was a kid, I wanted to be a writer. This was fueled by an intense reading habit: I would spend hours on the library looking for more Roal Dahl books, and later on, Tolkien and Ursula K. Le Guin. Nowadays I don't read as many books, and mostly non-fiction. I guess I’m more time deprived, and have a more utilitarian habit. Long form articles strike the right balance for me. They are longer and richer than a dopamine-inducing social media post, but I can still read them while in the toilet.

-

The source of truth shouldn't be figma, but the code

Jan 25 ⎯ Nth attempt to solve the designer/developer problem. An open source tool for designers to work with react components. Figma has been trying to convince designers that they are the source of truth, therefore, a handover process is required. And it's the developer job to translate designs into code. But the reality is that developers are convinced of the opposite. Figma is the just theory, but truth is whatever you ship to customers. And that’s code. This is another case of Segal’s Law: A man with a watch knows what time it is. A man with two watches is never sure

-

C02 consumption from your daily tech usage

Jan 24 ⎯ I love this kind of sites. It’s the deepest article I’ve seen on the topic of CO₂ emissions in tech, with interactive bits, graphs and calculators. It starts with this shocking calculation. A seemingly normal tech consumption is actually pretty costly in terms of CO₂ emissions. Last week, I streamed 20 hours of videos on Netflix, YouTube, and Canvas. I asked 50 questions to ChatGPT and made 532 Google searches. I sent 25 emails and 325 WhatsApp messages. From behind my screens, it did not feel like I was contributing to greenhouse gas emissions. Yet, the environmental impact of my online activity was real—it amounted to 1,447 grams of CO₂ equivalents[…] Over a year, this would add up to approximately 75 kilograms of CO₂ equivalents. To put that number in perspective, that is like: Driving 183 miles in a gas-powered car. Eating 6 servings of beef (25 grams of protein each). Charging a smartphone every day, until the year 2070.

-

Boring is good – Scott Jenson

Sep 19 ⎯ jenson.org

-

Why aren’t you a good fit?

Sep 18 ⎯ newsletter.antoniokov.com

-

Liquid Glass in the Browser: Refraction with CSS and SVG

Sep 18 ⎯ kube.io

-

Slow social media

Sep 17 ⎯ herman.bearblog.dev

-

How Coding Agents Actually Work: Inside OpenCode

Sep 16 ⎯ cefboud.com

-

Language Self-Play For Data-Free Training

Sep 16 ⎯ arxiv.org

-

AI Will Not Make You Rich

Sep 16 ⎯ joincolossus.com

-

The World in Which We Live Now

Sep 15 ⎯ nntaleb.medium.com

-

Chinese students are using AI to beat AI detectors

Sep 14 ⎯ restofworld.org

-

Setsum - order agnostic, additive, subtractive checksum - blag

Sep 14 ⎯ avi.im

-

The Case Against Social Media is Stronger Than You Think

Sep 14 ⎯ arachnemag.substack.com

-

Magical systems thinking

Sep 14 ⎯ worksinprogress.co

-

Clickless search and the internet of machines

Jan 23 ⎯ Interesting read about the repercussions of a “clickless search” world. We no longer use search engines to navigate through the web, but to get answers immediately. The author content ponders: The interesting question isn’t how to optimize for AI agents, but what kinds of human experiences are worth preserving in a world where machines do most of the talking.

-

Iconic: An alternative to Lucide Icons

Jan 23 ⎯ They seem to be optimized for smaller sizes. Only 200 are free, the rest are pro…

-

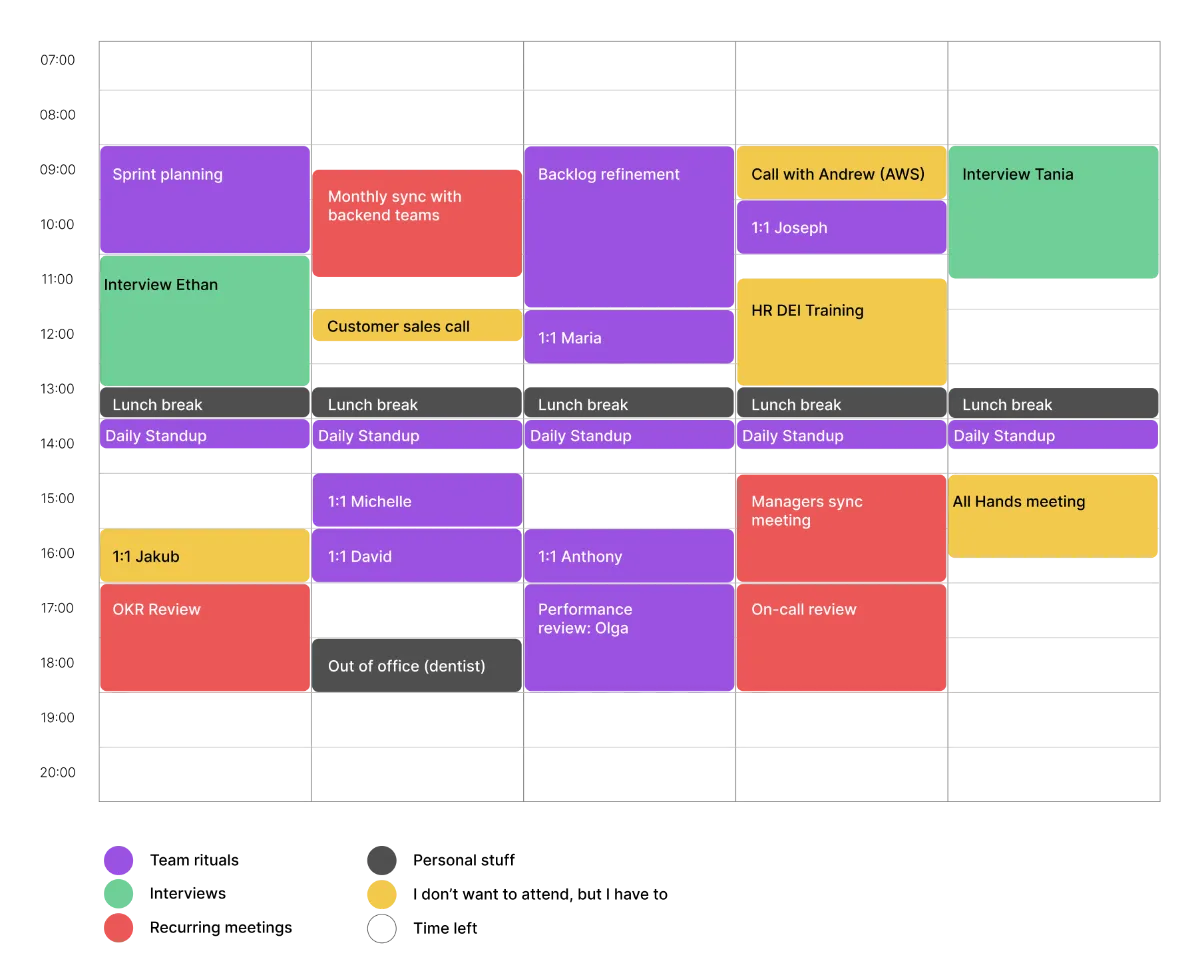

Show me your calendar!

Oct 24 ⎯ It’s Friday afternoon, and Jakub is at home preparing his third cup of coffee. He runs on caffeine because either the kids, or Pager-Duty, keep him up at night. He sprays the coffee beans with water since he saw it in a YouTube video, but he can’t tell the difference. “Moisture,” he thinks, “such a friendly word.” He checks the kitchen clock and realizes he is 1 minute late for his one-on-one meeting with Mike “The Fly”. Jakub is the director of Infrastructure at a large tech company in Illinois. Mike reports to him, and also happens to be a friend of his. “It’s not nepotism,” he always justifies. “Mike is solid, and he was the best candidate for that position.” They always start the one on one with some small talk. “How was your weekend?”, “And the kids?”, “Nice, send my regards to Angela.”. All very cordial, like when they were in college. But past the pleasantries, they both adopt their roles extremely seriously, like that Stanford prison experiment. And this week, Jakub has something important to discuss with Mike. Costs keep racking up, and Mike is not doing anything about it. “Look Mike, I know you are trying, and you are a good guy. Yeah, great guy. Very solid. But if you don’t put your shit together, I will have to let you go. And trust me, this is the last thing I want to do.” Jakub is originally from Poland and learned English by watching American TV. His way of speaking is very cinematic. He squints his eyes and talks with that whispery voice that no one uses in real life. “The costs keep being higher than expected, and management is not happy. My ass is on the line here.” Mike is not sure what to say. He rubs his hands nervously, and then he covers his face with them. The Fly. This is how he got the nickname, but no one ever told him, so he keeps doing it. “I am trying my best, Jakub. Really. I’m just swamped with meetings, you know? Keeping The Lights On and all that.” Jakub sighs. He will have to pull a Coaching Move on him. He hates doing this, but desperate times call for desperate measures. “It’s all-right Mike, I’m here to help. Just... Show me your calendar.” The air in the room is heavy. Mike is clearly tense and uncomfortable and hesitates for a moment before clicking the share screen button. “Can you see my screen?”. “Yes, I can. We always can. Why do we always ask?” A horrendous calendar shows on the screen. It’s a mess. Like an enraged Mondrian. “Jesus Maria!” Jakub yowls. That’s a common Polish way to express dismay, but they pronounce it like “MA-ree-ah”, not Maria. “This is a problem, Mike. This is a big problem. But we are going to fix it. We are going to fix it together.” Mike nods. He is ashamed. “I’m going to categorize all those meetings and see what we can do about it.” Jakub opens Google Sheets and starts typing stuff. “Can you see the problem?” “I can’t see anything, actually.” Mike interrupts him. “Oops, sorry. I’m sharing the wrong screen. Now… So, you know that your number one priority is to fix the costs. We agreed on this one month ago. And yet, you only have 13 hours a week for it. And most of it is divided into blocks of 30 minutes scattered here and there. You are not in control. The calendar is.” Mike looks down. “From next week onwards, you are going to block 5 hours every day, from 9am to 2pm. And you will tell everybody that you are not available during that time. Screw them. It’s your calendar, and if your calendar does not reflect your priorities, then they are not your priorities. Time is the most precious resource we have.” “Got it, Jakub. I will try. It makes a lot of sense when you put it this way… Now, just be honest with me. Is this some sort of Coaching Move?” “Sorry Mike, I have to leave you. I have to pick up the kids and I’m late already.” Fall came in, and the leaves turned yellow, orange, and brown. Mike The Fly successfully cut down the costs, and Jakub kept his job, but not for long, since Google poached him with a better offer. “That’s a hell of a logo. It will look good on my resume,” he thought. “And their offices are nice, too.” He brought in Mike and cashed $10.000 from a referral bonus. “He is solid,” he told the recruiters. “I’ve known him since college.” This time around, though, he would not report to him, which is better, since their friendship has weakened over the last year. Jakub started to drink more and more coffee, but he is not moisturizing the beans anymore: time is too precious. The job is more intense than ever, and his third kid is on the way. He is always stressed. Running late, running crazy. One day, they both met by the water cooler, “where serendipity happens,” as management would say. They started to do some small talk. All very cordial, like when they were in college. “How’s it going, Jakub?” “Pretty good, Mike,” he lies. “How about you?” “Much better, Jakub. Things are going great here at Google. Thanks for the referral, mate.” “You’re welcome, Mike. The bonus helped, but you know, I would do it anyway.” “I know... I know. Are you sure you are ok? You look tired.” “Yeah... you know, the kids.” “What about them?” “They are great. I love them above all else. But work is work, you know? I don’t find the way to balance it. I am trying to be a wonderful dad, but every day something else comes up. A conference, a meeting, a call.” He is mumbling, like he is trying to convince himself. Mike has never seen him like this. He starts rubbing his hands again, but this time he doesn’t cover his face. The Fly is gone; he is just The Mantis now. “This reminds me of something I read once,” Mike says. “The correct way to fill up a jar is to start with the rocks, then the pebbles, and you finish with the sand. If you do it the other way around, the rocks won’t fit. It looks like you know what’s important to you, but you are leaving it for the last.” Mike is not rubbing his hands anymore. He is smiling. They both know what comes next. “Jakub, why don’t you... Show Me Your Calendar?” The room goes dark and a lightning strikes across the room. A droplet falls from the water cooler, somewhere a bird takes off and flies away, and a leave falls from a tree. Jakub has been Counter Coached. Show me your calendar was one of the most interesting prompts I’ve been using as a CTO. Time management is one of the harder skills for managers to master and one of the most important ones. You can raise money, you can save it, you can invest it, and make it grow. But you can’t do any of that with time. Time just goes away, like water in a river. You either use it wisely, or waste it. In your one on ones, ask what the priorities were for the upcoming month. That already triggers the most interesting conversations. Top-down priorities are not always the same as bottom-up ones, and the truth often lies somewhere in the messy middle. Once you agree on the priorities, you can ask to see their calendar for the upcoming month. Things will get ugly: Business As Usual eats time like a black hole. People set up recurring meetings with good intentions, but when you let other people set your schedule, it’s not your schedule anymore. Ironically, at a personal level, I was failing at time management myself. It’s easier to solve someone else’s problems than your own, I guess. In my case, work was creeping up and taking over my calendar, despite telling myself that it was not my number one priority. This lead to neglecting health, friendships and hobbies, so I applied what I preached and contrasted my priorities with my calendar. I’m still trying to figure things out, but that’s for another story.

-

Why is everybody talking about sync engines?

Oct 16 ⎯ It's a sunny day in the countryside. The developers have gathered around the table and awkwardly engaging in small talk, which they hate. Meeting for the first time in real life, they subtly glance at each other's legs and bums, surprised by the unexpected difference in height. Especially Ethan, who has to bend to get out of the bus. Although all were pro-remote, they chose to spend a week together to tackle a shared problem: their product sucks. It's a task manager app called “ChoreCommander” that was disruptive 10 years ago when web apps were not a thing, but nowadays, they find themselves being replaced by more modern and faster products. The circle of life. David, the CTO, is willing to give up on his ideals. He has been a hardcore Ruby on Rails developer for more than a decade and he even has a tattoo of Matz on his left calf. “But perhaps”, he thinks for the first time, “it's time to embrace change.” “Rendering the whole world on each request, despite caching and JavaScript shenanigans, is holding us back,” he told the team in a sober tone. “…and we neglected offline and real-time collaboration. Nowadays, customers expect products to work like Gmail or WhatsApp, good on spotty connections, and without having to refresh to get updates.” Maria has been waiting for this moment for a long time. She has been a React advocate since 2004 despite the library not being that old, but she claims the ideas were all there on her head. She will not let this opportunity pass, and will finally get that juicy “Principal” title that she deserves. “I really think we should adopt React + Redux. You know, I’m a bit of a functional programmer myself, so I think immutability would really help towards our goals.” Dan is skeptical. “State shouldn't be global! Globals are evil!” he yells. “Didn’t we learn anything from Object Oriented Programming? State must be local to the components or it will be hard to reason about.” Tania sits in the corner, nodding her head as she begins to speak. “Doesn't this mean that we will have N+1 fetching problems on the frontend? Why not adopt react-query?” She takes a drag from her vape, holds it for five long seconds—an eternity—then exhales slowly before adding, “Everyone’s doing it.” Ryan is the oldest. Caressing his beard, is not sure what to think of any of this. He is worried that components, being structured as a tree, will lead to loading cascades. He has recently seen a talk by some “React guy” that claims that “data fetching needs to happen at the route level,” which makes sense to him. After all, that's how it has always been done in the backend. But he is shy and does not dare to contribute. Maria feels like everyone else’s opinions carry more weight, and her initial contribution was rather bland. Server Components come to mind, especially since Vercel—who scooped up all the React brains—seems to be heavily promoting them. “Have you guys heard about Server Components, our lord and sav…” Bam! Tadum! Crash. David just flipped the table, his face flushed with rage. He is desperate. As a CTO, he can't let this slide. He was ChoreCommander’s first engineer 10 years ago, and has vested all his shares. On paper, he is a millionaire, but if the MRR keeps going down, he will be left with nothing. He is the Silicon Valley equivalent of the Schrödinger's cat, both rich and poor at the same time. “Stop yapping! You’re all just bickering over what everyone else in the industry is doing, and your are not even talking about our users' actual concerns. What about offline functionality? What about real-time collaboration? Why is it so hard to make a f***ing to-do app? Every developer on the planet has made one!.” He is throwing things, he is losing it. Only Ethan can save them. Ethan stands up and bangs his head against the ceiling lamp. Oh Ethan, why are you so tall? He is not even 20 years old, but he talks with the confidence of a developer who started his career punching cards in the 60s. “You have no clue. All you web developers are a bunch of spoiled, entitled twats who’ve never solved a real engineering problem in your entire lives. I can't understand why you make everything so complicated, you are just converting database rows into html.” He’s got everyone’s attention now. They’ve all been thoroughly humiliated, but deep down, each of them secretly wishes they could just be like Ethan. “I come from a background in game programming, and we tackled this problem back in the ’90s.” He wasn’t even born then, but he always uses the Royal We. “What we need is a syncing engine, like in Duke Nukem 3D.” What follows is the talk that Ethan should have given to the team. Instead, he pedaled away on a stolen bicycle, developed a game that flopped commercially, and now roams the streets of San Francisco, high on fentanyl. Meanwhile, David and the rest of the team sold the company for peanuts but landed comfortable positions at the acquiring firm, earning twice as much while working half as hard. So, in the end, it probably didn’t matter. But if you’re interested in sync engines, read on. To learn how sync engines work, we are going to represent a scenario where two clients (Alice and Bob) do the following: Alice and Bob read a counter from the server concurrently. Alice increments the counter, and then Bob also does it. Alice refreshes the page. Let’s start by understanding how traditional web apps ⎯ nowadays called Multi Page Applications ⎯ work. We use diagrams to represent the evolution of state and UI over time, where dotted lines are ephemeral state, and normal lines persistent state. To read data, we request a “snapshot” of the server state over the network. We keep this state temporarily, meaning a refresh will fetch a newer snapshot. Writes are handled pessimistically, sent over the network, and only displayed to the user once the client receives server confirmation. This approach has worked for many years exceptionally well, offering simplicity and scalability thanks to its stateless design. However, it does come with several issues that might be unacceptable for your product: Reads always occur over the network, meaning offline reading isn't possible, and you'll face the latencies. Same goes for Writes, making all interactions feel laggy and without offline support. The stateless model can’t offer real-time collaboration, since the server doesn’t proactively push updates to the client. Let's try to solve these three issues incrementally. To do so, we are going to start by introducing a sync engine. A sync engine manages interactions with the network and maintains persistent storage for the local state. Both stateful and nasty operations that we usually implement within our components. By extracting those into a separate layer, we can free ourselves from it. Now that we have persistent storage, let’s cache reads. This is a technique often called Stale while re-validate. This minor change magically solves the first issue, dropping read latencies to zero (for stale data), and getting offline reads too. Let's move forward and allow the client to mutate the state locally. This is often called “Optimistic update” since the changes appear instantly, but need to be validated by the server. This change addresses the second issue by enabling users to write offline, and making writes feel instantaneous. This is the reason why video games feel so responsive: when you play, you expect to see the effects of your actions with zero latency, while in the background, everything syncs to the server for validation and propagation to other users. To sync local mutations to the server, there are two broad families of strategies: Serializable: The server only accepts operations from clients that match its current state. If a client attempts to sync a local mutation with stale data, the server will reject it, requiring the client to refresh its data and try again. This is the simplest model and found in many databases. Commutative: Mutations must be constructed or applied in a way that exhibits the commutative property, meaning the order of operations doesn’t matter. For example, instead of saying “set the counter to X,” you can use “increment the counter,” which is a commutative operation. Both CRDTs (Conflict-free Replicated Data Types) and OT (Operational Transformation) fall into this category. Let's keep improving our simple sync engine and add real-time collaboration. We just need to allow the server to ping changes to the client: With that, we have a fully working syncing engine. To be more specific, we've roughly described how Replicache works, which is one of the many sync engine solutions out there. We can stress test it by adding offline periods to it and see how it would behave. As expected, it supports offline reading, offline writing, and eventually both clients converge to the same state. It's a powerful architecture that liberates you from the gnarliest parts of building web applications. Sync engines feel as transformative as React was. I highly recommend everybody to try to build an app with this pattern. It’s a lot of fun. I’ve certainly glossed over many details regarding the actual implementation of a sync engine. We haven't discussed the specifics of mutation operations or how servers and clients negotiate which data needs to be fetched. This is merely a high-level introduction to the topic. If you want to learn more, I highly recommend reading the exceptional Matthew Weidner's article that goes deeper into the topic, and of course, the canonical Ink and Switch article on Local-first. I hope some parts of this article brought a smile to your face or even made you laugh. I like to sprinkle in hints to show that my articles are not generated by AI. So far, sense of humor seems to be working fine as a modern Turing test. Yours truly, Ethan.

-

All websites look the same: Let's bring the colors back!

Sep 02 ⎯ The Hot, mild, and cool cycle Art genres seem to go through the same patterns. They are born hot, vibrant and full of the energy an act of rebellion demands. Once they become more popular, they turn mild, expansive and sometimes bland. As the genre fades away in popularity, it becomes cool, niche and rational. It’s a cycle of visceral birth and rational death, like the old adage: If a person is not a liberal when he is twenty, he has no heart; if he is not a conservative when he is forty, he has no head. Let’s go back to the jazz age to illustrate the full spectrum: During the roaring 20s, youngsters would go to speakeasies to drink alcohol (which was prohibited), take drugs, and dance Charleston. Boom, rattle, bang! The beat of jazz was accelerated, syncopated and considered a "devil's music" for traditional music listeners. Hot! During the 30s, jazz became the most popular genre in the US. With radio broadcasting, big bands, and swing dancing. It dominated music as no other genre ever has. With new musicians entering the scene, the music grew more sophisticated, leading to burning hot bebop and later the cooler... cool jazz. Mild. By the late 50s, the genre already collapsed, giving way to rock'n'roll. Musicians became so good that they got out of touch with their audiences. Jazz turned more rational, technical and abstract, which made the genre adopt the "music for intelectual snobs" fame. You know a genre is in the last stage of their cycle when someone tells you: "if you don't like it, is because you don't understand it". Cool … Jazz, surprisingly, managed to stay interesting even at its peak. Unlike luxury brands, which are more popular and boring than ever, partly because it's believed that rebranding to sans-serif is necessary to increase their total addressable market. This article is about Web design But I digress. When it comes to web design, it feels like we're going through the same cycles: from the hot, colorful chaos of Geocities, through the mild intricacies of skeuomorphism, only to arrive at the cool, minimalist style that's popular today. You've probably heard the complain that all apps look the same nowadays. While this may be an exaggeration, it's true that most web apps share a similar modern, monochrome, and somewhat dull appearance. We are all trying to imitate the alphas of the current meta (Stripe, Notion, Linear, Figma) with a repertoire of astonishing techniques such as animations, 3D illustrations and CSS effects. Or just plainly assuming that “design has already been solved” and taking an off-the-shelve solution such as tailwind UI or shadcn. Nothing captures the zeitgeist of 2024 better than memes. I think the most relevant one is the “every website looks like Linear”. So my take is that we are in the late mild-stage, transitioning to the cool one. Tired: feelings & vibes. Wired: knowledge & skills. We are designing more generic web apps in order to maximize their total addressable market: Brave designs are more divisive and lead to a handful of lovers and haters, but a bland one appeals to everybody. Additionally, designers have polished their skills to signal status and compete with one another, inevitably distancing themselves from their audience. Skill issues and the birth of new genres I was never going to beat these girls on what they do best, the dynamic and the power moves, so I wanted to move differently, be artistic and creative because how many chances do you get that in a lifetime to do that on an international stage? Raygun – creator of the "kangaroo break dance" subgenre Once a genre's popularity starts peaking, it becomes increasingly difficult to remain relevant. All the practitioners compete to become the alpha, getting very, very good at it. It's tough out there. But some, feeling the pressure of their skill issues, grow increasingly frustrated, flip the middle finger to the status quo, and fork the genre into something new where they can make their mark. Dadaism rejected the rationalism of modern art, and punk flipped off the pretentiousness of rock 'n' roll—both arguably more entry-level than what came before. Perhaps Raygun was into something, and we are going to see animal-inspired dancing as a subgenre of break dance? Back to web app design. I'm not a designer by trade myself, and I feel massively under skilled to compete in the current meta. Hence, like Raygun, I refuse to compete within the same genre. I rebel against bold Inter headlines with a gradient mask, trying to steal the teenage-engineering look, the pixel-perfect border radius math, and those luscious, over-layered shadows you could practically make love to. I reject the rational, and serious design coolness to embrace the emotional, and playful one. And for me, the obvious first step is to say: "Colors welcome back, we've missed you." At this point, you might be wondering: Did I invent an entire theory of art genres just to justify my skill issues and my use of color? Hell yeah! I would cross the rocky mountains riding an army of bisons to ransack San Francisco before learning how to design those fancy buttons that shed light when you hover them—although this is actually not true, I'm pretty chill and I do like learning things, but I hyperventilated while writing and I didn't want to break the flow. Welcome back colors! I see a lot of designers reject the use of color. Some will raise accessibility concerns, which are valid if your affordances rely solely on color. But when used decoratively, they can enhance your design without compromising accessibility. Others will claim that designing with colors is harder. That's true. Desaturated or monochrome palettes are like jeans and a t-shirt—they’ll always look fine. But as soon as you start playing with colors, there are more ways to mess things up. In the rest of this article, I'll walk you through my process for designing with color, which might just help you give it a shot. An easy way to create a color system is to constraint yourself to only use: One “black” color One “white” color One “gray” scale N color scales Hues First step is to pick the hues. Many articles will try to shovel a lot of science stuff down your throat to make it look like picking hues is a science. But in reality, it's mostly vibes and figuring out why some things look nice after the fact. Like most artistic learning, just look around and once you see something you like, try to figure out why. To explore ideas, you can use books such as Interaction of Color, or the Dictionary of Color Combinations. I find that starting with hues makes the process a lot easier, since the rest of the choices tend to be more about utility than creativity. For example, while designing fika, I've based the whole design on five hues: emerald, indigo, amber, rose and tangerine. I choose sophisticated names to feel better about myself: green, blue, yellow, pink and orange are for normies. Do these colors follow any formula like Triadic or Tetradic colors? I have no idea. I just wanted colors that “felt” different enough, and math cannot be used to calculate this since it’s a social thing. Different people categorize colors differently, but clearly our biggest categories are green and blue—so much that we used to put them both in the same “grue” category. a map of colors with their categories by xkcdContrast Contrast defines how distinct two colors appear from each other, and there are many ways to measure it. The simplest method is WCAG2, but its simplicity makes it flawed because it overlooks the fact that different colors can have different perceived lightness. different hues with their perceived lightnessTo avoid false positives (and negatives) such as the infamous "orange button problem", there is a new way to measure contrast called APCA. I highly recommend adopting it. To define contrast, we'll create lightness curves that apply across all color scales. This way, UI elements can use different hues while maintaining a consistent contrast. This was historically hard to achieve because, again, perceived lightness is different for each hue. But luckily, there is also a new color space called OKLCH which addresses this problem. OKLCH is a color space similar to HSL (Hue, Level, Saturation), but the C stands for Chroma (which is more or less like Saturation), and the L is the Perceptual Lightness. This means that you can finally craft color scales with the same contrast and "colorfulness" characteristics, without guessing. With all these new tools, working with colors nowadays is fantastic! Lightness To create a lightness curve, you want to follow an S-shape. This approach maximizes the contrast between dark and light tones, as most UI elements will use colors at the extremes. Middle tones are seldom used due to their lack of sufficient contrast. Saturation / Chroma Chroma follows a normal-ish distribution instead, with very low levels in the light and dark tones, and higher levels in the middle tones to compensate for their lack of light contrast. I like to add a bit more saturation to the dark tones, but that's just my personal preference. The downside is that it breaks symmetry. Symmetry is important if you are planning to reuse the same scales for a dark theme. In my experience, though, that dream doesn’t hold up because you can’t just reverse the colors and expect the light/shade metaphors to work the same. Also, I find more pleasant when dark tones are more vibrant. comparing saturation palettescomapring asymmetrical saturation palettesOne exception to this is your “gray” scale, which you will use for neutral elements such as backgrounds or long-form text, which need a much flatter saturation curve. When you decide about that scale, you will either drop saturation altogether, or have a very flat curve for a warmer or colder vibe. OKLCH Once you have the hues and the lightness/saturation curves, it's time to combine them. One challenge you may face is that not all hues are made equal, and some fall short in the darks or the light tones. Luckily OKLCH allows for an extended range of colors P3 which can ease this limitation, but, expect some tiny adjustments since some colors (like cyan or orange) have extremely very narrow ranges. oklch picker screenshotIf this article seems too much and you don't know where to start, I highly recommend downloading Harmony as a starting point. It's a collection of color scales created by the talented people at Evil Martians. Harmony has symmetric contrast, which makes them a good fit if you plan to add a dark theme. Check their article on OKLCH and also their fantastic color picker. If you work with Figma, I also highly recommend using the okcolor and Polychrom Figma plugins to workaround the lack of support for OKLCH and APCA contrast. Awesome. You have a color system ready to go and it's time to implement it. Let's delve dive into it! (every article should contain a clue of being written by a human, here’s mine) Coding a color palette I'm aware that all the cool kids use tailwind since "they've solved CSS and there is no need to reinvent the wheel". But I still like using vanilla-extract. It fits better my mental model and I feel more productive with it. I hope this doesn't make you angry and you can keep reading this article. We can all learn from each other. First thing we do is to create a colors.ts file with a definition of the colors, types and some convenient functions to operate it: The most useful function is mapHues. It's a function that returns an object for every hue in your color system. This is particularly useful when creating variants, since it helps us define the code once for all the hues. This is how you use it in your vanilla-extract CSS files: And then you can easily use it in your component like this: Which results in the following components: I also like to create toggleColor which is a function o automatically finds us the symmetric lightness for a given color. This is very useful for components that need to use the high or low end of your color palette, depending on whether they sit on top of a light or dark background. Now we can use this to “toggle” the lightness: And this is how this component looks like for all the combinations of hue and dark: Wrap up This was a long one! I hope this post convinced you to fight the cool and bring some joyful colors back to the internet.

-

Fear of over-engineering has killed engineering altogether

Jul 26 ⎯ In the last 20 years, we have seen how engineering has become out of fashion. Developers must ship, ship, and ship, but, sir, please don’t bother them; let them cook! There are many arguments that go like “programming is too complex; it is not a science but an art form, so let’s YOLO it." And while there is a certain truth to that, I would like to make a counterargument. Where does it come from? If you’ve been in tech for long enough, you can see the pendulum always swinging from one end to another. The more you've seen, the more you realize that interesting things happen in the middle. In the land of nuance and “it depends." Before the 2000s, academics ruled computer science. They tried to understand what "engineering" meant for programming. They borrowed practices from other fields. Like dividing architects from practitioners and managing waterfall projects with rigorous planning. It was bad. Very bad. Projects were always late, too complex, and the engineers were not motivated by their work. This gave way to the creation of the Agile Manifesto, which disrupted not only how we program, but also how we do business in tech altogether. Both Lean Startup and later the famous YC Combinator insisted on moving fast, iterating, and not worrying about planning. To make things worse, engineers took Donald Knuth’s quote “Premature optimization is the root of all evil” and conveniently reinterpreted it as “just ship whatever and fix it later… or not." I do think the pendulum has gone too far, and there is a sweet spot of engineering practices that are actually very useful. This is the realm of Napkin Math and Fermi Problems. The right amount of engineering To predict where a planet will be on a date, it's faster to model and calculate than to wait for the planet to move. This is because humans have a shortcut. It's called mathematics, and it can solve most linear problems. But if I want to predict a complex system such as cellular automata, we have no shortcut. There is no mathematics – and perhaps there will never be – to help us bypass the whole computation. We can only run the program and wait for it to reach the answer. Most programs are complex systems; hence the resistance to engineering at all. Just run it and we shall see. Yet, they all contain simple linear problems that, if solved, are shortcuts to understanding whether they make sense to be built at all. A very little cost that can save you months of work. Those linear problems are usually one of the three: Time: Will it run in 10 ms or 10 days? This is the realm of algorithmic complexity, the speed of light, and latencies. Space: How much memory or disk will it need? This is the land of encodings, compression, and data structures. Money: And ultimately, can I afford it? Welcome to the swamp of optimizations, cloud abuse, and why the fuck I’ve ended up living under a bridge. And of course, the three are related. You can usually trade off time and space interchangeably, and money can usually buy you both. Fermi problems and Napkin Math One of the things that bothers most people is “not knowing the numbers." Predicting the future without past data can be very stressful. But, once you get used to making things up, you will see that what matters is not the numbers, but the boundaries. One of the most well-known Fermi problems, infamously used in some job interviews, is to guess how many piano tuners there are in New York. You won’t get the correct number, but one can be certain that the number must be between 10 and 10,000. You can get closer if you know how many people live in New York (8M). If 1% own a piano (80,000) and 1 tuner can serve 100 customers a year, then the upper bound is about 800, or 1,000 to round it up. Despite those guessed boundaries being orders of magnitude apart, it may be enough to convince you not to build a 1 euro/month app for that niche. You start by writing down extremely pessimistic assumptions, things that likely fall in the p99. For instance, if you want to calculate how much storage you need to store a book's content, assume a book has 5,000 pages. Most books will have less than that, so if the resulting calculation is positive, then you are more than good to go. Calculations boil down to simple math: adding and multiplying your assumptions. Nothing fancy. But for other calculations, you will need to know benchmarks or details of algorithms and data structures. For instance, if you are trying to estimate how much money you need to train an LLM model, knowing how transformers work will help. It lets you calculate the memory needed. I recommend bookmarking some cheat sheets and keeping them around. I usually only do a worst-case scenario calculation, but if you want to do interval calculations, you can use tools like guesstimate. Keep the calculations around since once you start having real data, you will want to verify the assumptions and update the priors. Example of the Napkin Math at fika As an example, I will show the calculations I did while building fika to determine what was possible, what was not, and what ended up being up to date. The main assumption is that a p99 user (which I modeled after myself) would have around 5,000 bookmarks in total and would generate 100 new ones a month. According to the HTTP Archive, the p90 website weighs ~9MB, which is very unfortunate because it makes storage (R2) costs too high. But if you look deeper into the data, most of this weight goes into images, CSS, JavaScript, and fonts. I could get clever with it and get rid of most of that content with Readability, compress images, and finally gzip it all. This is a requirement that I didn’t think of before starting the project, but it became obvious once the numbers were on the table. I also calculated whether I could afford to use Inngest or not. The user price was too high until I discovered that batching most events could reduce the cost to a manageable amount. I've also evaluated two more fantastic vendors. Microlink fetches the bookmark's metadata, and Browsercat provides a hosted Playwright solution. Unfortunately, their pricing model wouldn’t fit my use case. I wanted to price the seat at $2, and these two providers would eat up all the margins. Later I explored implementing hybrid search. OpenAI's pricing at the time was $0.10 for a million tokens, which meant a monthly $0.60 per user. It was too pricey, but some months later they released a new model for only $0.02. Even though that price was now making semantic search possible, I had already migrated the search to the client. With the release of snowflake-arctic-embed-xs, I wanted to see if I could embed all the bookmarks in memory. This was needed since implementing a disk-based vector database was not in scope. I calculated that it would need ~350MB, which is not great. But this space is moving fast, and small models are becoming more attractive, so I will wait a bit to see how it develops. Lastly, one of my biggest fears about building a local-first app was ensuring that the users would be able to hold all the data on the client side. I’ve focused only on bookmarks, since this is where most of the weight will likely go. Origin Private File System (OPFS): To read the bookmarks offline, I want to save a copy on the user device. Saving them all, in the worst-case scenario, is ~3GB. This means that with storage quotas of 80% in Chromium, I could support any device with more than 4GB of storage. Nice. In memory full text search: I wanted to know whether I could have all the bookmark bodies in memory and operate a BM25-based search with orama. I don’t know much about the inverted trees and other data structures of full-text search databases. But, if we assume there is no overhead (unlikely), having all the bookmarks' text in memory would take around ~350MB. I didn't discard this approach, but this is definitely something I need to look deeper into. I'm currently exploring whether using SQLite + FTS5 would allow having those indexes on disk instead of in memory. Current results I've received the first 200 signups, proving that some assumptions were too pessimistic. ~1000 → ~200 stories a month/user: It’s still early, but obviously most users still have few bookmarks and subscribe to very few feeds. This number alone makes the cost per user go down to $0.02, which unlock; removing the paywall altogether without going bankrupt. 0.36MB → 0.13MB per bookmark: It turns out that bookmarks can be compressed more than I initially thought. Using WebP, limiting the size, and getting rid of all CSS/JS/fonts is making bookmarks very lightweight. 5% → 3% overlap: My intuition says that this number will go higher. As more people join the platform, the likelihood that you will bookmark a story that someone else has already bookmarked should go higher. But at the moment, users are more unique than I thought. 20% → 108% feeds per bookmark: This means that bookmarking one story finds, on average, 1.08 feeds. How can this be? Is RSS that popular that websites include more than one? Nope. This is one of the biggest surprises, and it was a complete miscalculation on my end. It turns out that the system has feedback loops. A bookmark recommends a feed. The feed contains stories. Those stories discover a different feed. For instance, subscribing to Hacker News is a very fast way to discover many other feeds. It’s too early to judge the usefulness of the numbers per se, but making the exercise was a very important step to drive the architecture. It took me only one hour to put an Excel together. A very low cost compared to all the hours I spent implementing fika. Coda I hope after this post I encourage you to check the fridge before cooking. Don't be afraid to do some basic calculations, and doing so will not make others see you as a lesser alpha. It’s not over-engineering; it’s not premature optimization. It’s a very basic form of hedging, with a ridiculously low cost and a potentially bonkers return. Because the best code is always the one that is never written. Cheers, Pao

-

The Last Days Of Social Media

Sep 14 ⎯ www.noemamag.com

-

GitHub - sindresorhus/type-fest: A collection of essential TypeScript types

Sep 13 ⎯ github.com

-

The crawl-to-click gap: Cloudflare data on AI bots, training, and referrals

Sep 12 ⎯ share.google

-

GitHub - rednote-hilab/dots.ocr: Multilingual Document Layout Parsing in a Single Vision-Language Model

Sep 12 ⎯ share.google

-

ChatGPT Memory and the Bitter Lesson

Sep 12 ⎯ www.shloked.com

-

Generative and Malleable User Interfaces with Generative and Evolving Task-Driven Data Model | Proceedings of the 2025 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems

Sep 12 ⎯ dl.acm.org

-

You Don't Need Animations

Sep 11 ⎯ emilkowal.ski

-

RSL

Sep 11 ⎯ rslstandard.org

-

Defeating Nondeterminism in LLM Inference

Sep 11 ⎯ thinkingmachines.ai

-

An Interactive Guide to TanStack DB | Frontend at Scale

Sep 10 ⎯ frontendatscale.com

-

Real-Time Detection of Hallucinated Entities in Long-Form Generation

Sep 10 ⎯ arxiv.org

-

Paper page - Reverse-Engineered Reasoning for Open-Ended Generation

Sep 10 ⎯ huggingface.co