Pao Ramen

-

Can it run Doom?

Sep 12 ⎯ One of my favorite activities with my kids is visiting science museums, especially the interactive ones. Pull a lever, twist a knob, press a button, and watch the effects of gravity, light, or fluid dynamics come to life. It’s so much better than just reading about it! Content creators have recently started applying the same approach to long-form articles. Some concepts are simply better explained through experimentation. It’s more engaging and rewarding for the reader. Unfortunately, most publishing platforms don’t make it easy to create this kind of content. Right now, it’s mostly developers who have access to it. I want to change that by introducing a new feature at fika: Snippets. Snippets let you easily embed interactive elements within your article. For now, you’ll need to code the Snippets yourself or rely on your LLM of choice. I may integrate this into the product later, but let me show you how it works with an example. Imagine I want to represent a double pendulum and it’s chaotic nature. I will prompt in ChatGPT. Create an html document with a simulation of a double pendulum that leaves a trail of their edge. Transparent background, 400px height. The pendulum is black and the traces are pastel blue Once it’s done, click on copy code and then I paste it inside an article snippet. It looks like this: Beautiful! I’m a developer myself, but I don’t know the physics of pendulums by heart. So once we’ve demonstrated that you can add Snippets to your articles, the next question is whether the title of this article is just clickbait, or if it actually delivers. Can it run Doom? Yes of course!

- fika

-

Local-first search

Jul 31 ⎯ I hear a lot of people are debating whether to adopt a local‑first architecture. This approach is often marketed as a near-magical solution that gives users the best of both worlds: cloud-like collaboration with zero latency and offline capability. Advocates even claim it can improve developer experience (DX) by simplifying state handling and reducing server costs. After two years of building applications in this paradigm, however, I’ve found the reality is more nuanced. Local-first applications do have major benefits for users but I think the DX claims fall off a cliff as your application grows in complexity or volume of data. In other words, the more state your app manages, the harder your life as a developer becomes. DX differences between local-first and cloud-based applicationsOne area I struggled with the most was implementing full-text search for my Fika, my local-first app that I used to write this very same blog post. Now that I’m finally happy with the solution, I want to share the journey with y’all to illustrate how local-first ideals can be at odds with practical constraints. Search at Fika Fika is a local-first web application built with Replicache (for syncing), Postgres (as authoritative database), and Cloudflare Workers (as the server runtime). It’s a platform for content curators, and it has three types of entities that need to be searchable: stories, feeds, and blog posts. A power user can easily have ~10k of those entities, and each entity can contain up to ~10k characters of text. In other words, we’re dealing with on the order of 100 million characters of text that might need to be searched locally. To deliver a good search experience for Fika’s users, I had a few specific requirements in mind: Good results: This sounds obvious, but many search solutions don’t actually deliver relevant results. In information retrieval terms, I wanted to maximize Recall@k, roughly, the fraction of relevant documents that appear in the top k results. Fuzziness: We don’t always remember the exact word we’re looking for. Was it “index” or “indexing”? Does décérébré really have 5 accents? The search needs to tolerate small differences in spelling/word forms. Techniques like stemming, lemmatization, or more generally typo-tolerance (a form of fuzzy search) help ensure that minor mismatches don’t result in zero hits. Highlighting: A good search UI should make it obvious why a result matched the query. Showing the matching keywords in context (highlighted in the result snippet) helps users understand why a given item is in the results. Hybrid search: This is a fancy term for combining traditional keyword search with vector-based semantic search. In a hybrid approach, the search engine can return results that either literally match the query terms or are semantically related via embeddings. The goal is to get the precision of keyword search (sparse) plus the recall of semantic search (dense). Local-first: Search is one of the main features of Fika, and it needs to work reliably and fast under any network condition. Other excellent bookmark managers like Raindrop are struggling to support offline, since they are based on a cloud-based architecture. This is a major differentiation point for Fika. With these goals in mind, I iteratively tried several implementations. The journey took me from a purely server-based approach to a fully local solution. Let’s dive in! First attempt: Postgres is awesome ok My first attempt was decidedly not local-first: I just wanted a baseline server-side implementation. I drank the Kool-Aid of “Postgres can do everything out of the box” and implemented hybrid search directly in Postgres. The idea was seductive: if I could make Postgres handle full-text indexing and vector similarity, I wouldn’t need a separate search service or pipeline. Fewer moving parts, right? First architecture: Pure PostgresWell, reality hit hard. I ran into all sorts of quirks. For example, the built-in unaccent function (to strip accents for diacritic-insensitive search) isn’t marked as immutable in Postgres, which means you can’t use it in index expressions without jumping through hoops. Many other rough edges cropped up turning what I hoped would be an “out-of-the-box” solution into wasted time reading PG docs and StackOverflow. In the end, I did get a Postgres-based search working, but the relevance of the results just wasn’t great. Perhaps one reason is that vanilla Postgres full-text search doesn’t use modern ranking algorithms like BM25 for relevance scoring, its default ts_rank is a more primitive approach. This was 2 years ago, so it would be worth trying again though, since ParadeDB’s new pg_search looks very promising! Second attempts: Typesense Having been humbled by Postgres, my next move was to try Typesense, a modern open-source search engine that brands itself as a simpler alternative to heavyweight systems like ElasticSearch. Within a couple of hours of playing with Typesense, I had an index up and running. It pretty much worked out of the box. All the features I wanted were supported with straightforward configuration and the developer experience was night-and-day compared to wrestling with Postgres. Second architecture with TypesenseTo integrate Typesense, I did have to modify the pipeline so that whenever a story/feed/post was created or updated in Postgres, it would also be upserted into the Typesense index (and deleted from the index if removed from the DB). But this was pretty manageable, far easier than dealing with Postgres. Sometimes we obsess with simple architectures that end up being harder to deal with. Simple ≠ easy. At this point, I had a solid server-side search solution. However, it wasn’t local. Searches still had to hit my server. This meant no offline search, and even though Typesense is fast, it couldn’t match the latency of having the data on device. For Fika’s use case (quickly pulling up an article on a phone while offline or on a spotty connection) I wanted to push further. It was time to bring the search engine, into the browser. <suspense music> Third attempt: Local-first with Orama If you’ve ever looked into client-side search libraries, you might have noticed the landscape hasn’t changed much in the last decade. We have classics like Lunr.js or Elasticlunr, but many are unmaintained or not designed for the volumes of data I was dealing with. Then I came across a relatively new, shiny project called Orama. Orama is an in-memory search engine written in TypeScript that runs entirely in the browser. The project supports full-text search, vector search, and even hybrid search. It sounded almost too good to be true, and despite the landing page not being ugly (always a bad sign), I decided to give it a shot. Third architecture: Local-first oramaTo my surprise, Orama delivered on a lot of its promises. Setting it up was straightforward, and it indeed supported everything I needed. I was able to index my content and perform both keyword searches locally. This was pretty mind-blowing: I had Elasticsearch-like capabilities running in the browser, on my own data, with no server round-trip. Awesome. But, and they say everything that comes before a “but” is bullshit. There were new challenges. The first issue was data sync and storage. To get all my ~10k entities into the Orama index, I needed to feed their text content to the browser. Fika uses Replicache to sync data, but originally I wasn’t syncing full bodies of articles to the client (just titles and metadata). Turns out that storing tons of large text blobs in Replicache’s IndexedDB store can slow things down. Replicache is optimized for lots of small key/value pairs and shoving entire 10k-character documents into it pushes it beyond its sweet spot (the Replicache docs suggest to keep key-value size under 1MB). To work around this, I adopted a bit of a hack: I spun up a second Replicache instance dedicated to syncing just the indexable content (the text of each story/feed/post). This ran in parallel with the main Replicache (which handled metadata, etc.) on a Web Worker. With this separation, I could keep most of the app snappy, and only the search-specific data sync would churn through large text blobs. It worked… sort of. The app’s performance improved, but having two replication streams increased the chances of transaction conflicts. Replicache’s sync, because of it’s stateful nature, demands a strong DB isolation level, so more concurrent data meant more retries on the push/pull endpoints. In other words, I achieved local search at the expense of a more complex and somewhat more brittle syncing setup. I told you the DX gets more complicated at the limit! And we are just getting started. I also planned to add vector search on the frontend to complement Orama’s keyword search. First I tried using transformers to run embedding models in the browser and doing all semantic indexing on-device. But an issue with Vite would force the user to re-download the ML model on every page load, which made that approach infeasible. This issue has been solved now, so it remains an experiment to try again. Later I tried generating the embeddings on the server and syncing them to the client, but the napkin math was not napkin mathing: With a context length of 512 tokens, most documents (~10k chars each) would need at least 5 chunks to cover their content (10,000 chars / ~4 chars per token ≈ 2,500 tokens, which is ~5 × 512-token chunks). That means ~5 embedding vectors per document. For ~10k documents, that’s on the order of 50k vectors. If each embedding is 768 dimensions (a common size for BERT-like models), that’s 38.4 million floats in total. 38.4M floats, at 4 bytes each (32-bit float), would be ~150 MB of raw numeric data to store/transmit. And because we use JSON for transport, it would encode these floats as text. The actual payload would balloon to somewhere between ~384–500 MB of JSON 😱 (each float turned into a string with quotes/commas overhead, e.g. "0.1234,"). That’s a lot to sync, store, and keep in memory. Could we quantize the vectors or use a smaller embedding model? Sure, a bit: for example, Snowflake’s Arctic Embed XS model has 384-dimensional vectors, which would reduce the size. But we’d still be talking hundreds of MB of data. And the more we started optimizing for size (bigger context lengths, aggressive quantization, etc.), the more the semantic search quality would degrade. So, I decide to yank the wax stripe and toss the hairy dream of local semantic search straight into the trash. In fact, to really convince myself, I ran two versions of Fika for a while: one version used my earlier server-side hybrid search (Typesense with both keywords and vectors), and another used local-only keyword search (Orama). After a couple of weeks of using both, I came to a counterintuitive conclusion: the purely keyword-based local search was actually more useful. The hybrid semantic search was, in theory, finding related content via embeddings, but in practice it often lead to noisier results. As I was tuning the system, I found myself giving more and more weight to the keyword matches. Perhaps it’s just how I search. I tend to remember pointers to the things I look for and rarely look for abstract terms. I could have bolted on a re-ranker to refine the results, but that would be a hassle to implement locally. And more importantly, the hybrid results sometimes failed the “why on earth did this result show up?” test. For example: Looking for a recipe I typed “bread” and I got an AI paper with nothing highlighted… oh wait, I see... there’s a paragraph in this AI paper that mentions croissants. Are croissants semantically related to bread? Opaque semantic matches can sabotage user trust in search results. In a keyword search, if I search a keyword, I either get results that contain those words or I don’t. It’s clear. With semantic search, you sometimes get results that are “kind of” related to your query, but without any obvious indication why. That can be frustrating. So I ultimately dropped the hybrid approach and went all-in on Orama for keyword search. Immediately, the results felt more focused and relevant to what I was actually looking for. Bonus: the solution was cheaper (no need to generate embeddings) and simpler to operate in production. However, I haven’t addressed the elephant in the room yet: Orama is an in-memory engine. Remember that ~100 MB of text? To index that, Orama was building up its own internal data structures in memory, which for full-text search can easily be 2–3× the size of the raw text. I was personally allocating ~300 MB of RAM in the browser just for the search index. That’s ~300 MB of the user’s memory just in case they perform a search during that session, and many sessions, they might not. What a waste. That’s far from good engineering. But we are not done with the bad news. On the server, you can buy bigger machines with predictable resources that match your workload. But with local-first, you have to deal with the device of your customer: For low-end devices (phones) the worse was not the memory overhead but the index build time. Every time the app loaded, I’d have to take all those documents out of IndexedDB and feed them into Orama to (re)construct the search index in memory. I offloaded this work to a Web Worker thread so it didn’t block the UI, but on a better-than-average mobile phone (my Google Pixel 6), this indexing process was taking on the order of 9 seconds. Think about that: if you open the app fresh on your phone and want to search for something right away, you’d be waiting ~9 seconds before the search could return anything. That’s worse than a cloud-based approach, and not an acceptable trade-off. I tried to mitigate this by using Orama’s data persistence plugin, which lets you save a prebuilt index to disk and load it back later. Unfortunately, this plugin uses a pretty naive approach (essentially serializing the entire in-memory index to a JSON blob). Restoring that still took on the order of seconds, and it also created a huge file on disk. I realized that what I really needed was a disk-based index, where searches could be served by reading just the relevant portions into memory on demand (kind of like how SQLite or Lucene operate under the hood). Last and final solution: FlexSearch As if someone was listening my frustrations, around March of 2025 an update to the FlexSearch library was released adding support for persistent indexes backed by IndexedDB. In theory, this gave exactly what I wanted: the index lives on disk (so app reloads don’t require full re-indexing), and memory is used only as needed to perform a search (and in an efficient, paging-friendly way). I jumped on this immediately. The library’s documentation was thorough, and the API was fairly straightforward to integrate. I basically replaced the Orama indexing code with FlexSearch, configuring it to use IndexedDB for persistence. The difference was night and day: On a cold start (new device with no index yet), the indexing process would incrementally build the on-disk index. This initial ingestion is still a bit heavy (it might take few minutes to pull all the data and index it), but it’s a one-time cost per device. On subsequent app loads, the search index is already on disk and doesn’t need to be rebuilt in memory. A search query will lazily load the necessary portions of the index from IndexedDB. The perceived search latency is now effectively zero once that initial indexing is done. Even on low-end mobile devices, searches are near-instant because all the heavy lifting was done ahead of time. Memory usage is drastically lower. Instead of holding hundreds of MBs in RAM for an index that might not even be used, the index now stays in IndexedDB until it’s needed. Typical searches only touch a small fraction of the data, so the runtime memory overhead is minimal. (If a user never searches in a session, the index stays on disk and doesn’t bloat memory at all.) At this point, I was also able to simplify my syncing strategy. I no longer needed that second Replicache instance continuously syncing full document contents in the background. Since the FlexSearch index persists between sessions, I could handle updates in an incremental way: I set up a lightweight diffing mechanism using Replicache’s experimentalWatch API. Essentially, whenever Replicache applies new mutations from the server, I get a list of changed document IDs (created/updated/deleted). I compare those IDs to what’s already indexed in FlexSearch. The difference tells me which documents I need to add to the index, which to update, and which to remove. Then, for any new or changed documents, I fetch just those documents’ content (lazily, via an API call to get the full text) and feed them into the FlexSearch index. This acts as an incremental ingestion pipeline in the browser. On a brand new device, it will detect that “no documents are indexed” and then start pulling content in batches until the index is fully built. After that, updates are very small and fast. This approach turned out to be surprisingly robust and easy to implement. By removing the second Replicache instance and doing on-demand content fetches, I reduced a lot of the database serialization conflicts. And because the index persists, even if the app crashes mid-indexing, we can resume where we left off next time. The end result is that search on Fika is now truly local-first: it works offline, it has essentially zero latency, and it returns very relevant results. The cost is that initial ingestion time on a new device and some added complexity in keeping the index in sync. But I’m comfortable with that trade-off. Conclusion As I mentioned at the beginning, the developer experience of building local-first software becomes more challenging as you push for more complex, data-heavy features to the client side. Most of the time, you can’t YOLO it. You have to do the math and account for the bytes and processing time on users’ devices (which you don’t control). In a cloud-based architecture you should also care about efficiency, but traditionally many web apps get away with sending fairly small amounts of data for each screen, so developers are less forced to think about, say, how many bytes a float32 in JSON takes up. In the end, I would dismiss DX claims and only recommend building local-first software if the benefits align with what you need: It resonates with your values. If you care about data ownership and the idea that an app should keep working even if its company go on an “incredible journey”. Your business model revolves around “backing up your data” instead of “lending your data”. The performance characteristics match your use case. Local-first often means paying a cost up front (initial data sync/download, indexing, etc.) in exchange for zero-latency interactions thereafter. Apps that have short sessions need to optimize for fast initial load times. But apps that have long sessions and a lot of interactions, benefit from local-first performance characteristics. You need the out-of-the-box features it enables. Real-time collaborative editing, offline availability, and seamless sync are basically “free” with the right local-first frameworks. Retrofitting those features onto a cloud-first app is extremely difficult. If none of the above are particularly important for your project, I’d say you can safely stick to a more traditional cloud-centric architecture. Stateless will always be easier than stateful. Local-first is not a silver bullet for all apps, and as I hope my story illustrates, it comes with its own very real trade-offs and complexities. But in cases where it fits, it’s incredibly rewarding to see an app that feels as fast as a native app, works with or without internet, and keeps user data under the user’s control. Just get your calculators ready, and maybe a good supply of coffee for those long debugging sessions. Good luck, and happy crafting!

- local-first

- search

- +1

-

AI is eating the Internet

Jul 28 ⎯ “You see? Another <something> ad. We were just talking about this yesterday! How can you be so sure they’re not listening to us?” – My wife, at least once a week. Internet advertising has gotten so good, it’s spooky. We worry about how much “they” know about us, but in exchange, we got something future generations may not: free content and services, and a mostly open Internet. It is unprecedented Faustian bargain, one that is now collapsing. A Memory of Summer: The Ad-Based Utopia At the epicenter of the modern Internet sits Google. Forget the East India Company, Google, with an absurd +$100B in net income, is arguably the most successful business in history. By commanding nearly 70% of the global browser market and 89% of the search engine market, they dominated Internet through sheer reach. How did this happen? A delicate balance of incentives where every player on the Internet got exactly what they wanted: Consumers enjoyed free access to virtually unlimited information and online services. Content creators got a steady stream of visitors flowing from search engines, which they could monetize via ads or conversions. Advertisers gained demand for their products at a reasonable price, thanks to unprecedented targeting precision. Google crawled the entire Internet, and site owners didn’t just allow it: they optimized for it. Users found what they wanted (most of the time, for free), while advertisers happily footed the bill because digital ad targeting finally began to solve the old John Wanamaker dilemma: “Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is I don't know which half.” Later on, Meta (then Facebook) doubled down on the same ad-driven premise. The social graph plus cross‑device identity made its targeting scary good. And advertisers flooded in. Google saw the threat but Zuck went full Carthago delenda est. By the late 2010s, the Google-Facebook duopoly ran the ad‑funded Internet: Google caught “I’m looking for it” intent; Meta created “make me want it” demand, and both printed money. Winds of Winter: The Transformer revolution Even the mightiest empires fall, and Google unknowingly sowed the seeds of its own undoing. In 2017, Google researchers published “Attention is all you need,” introducing the Transformer architecture. Originally meant to improve translation services, this innovation also led to enhance search quality with models like BERT. When OpenAI’s ChatGPT launched (as a free research demo in late 2022), it spread like wildfire, reaching 100 million users in just two months. The fastest adoption of any consumer application in history. Suddenly, millions of people started replacing the search box with a chat box. Why type a query and sift through ten blue links (from which 2-5 are ads) when an AI could synthesize an answer for you? The Internet’s longstanding equilibrium began to topple. Today’s landscape is one of turmoil, change, excitement, and fear. Content is no longer traded for traffic; content has become training data. And data is the fossil fuel of AI. This shift has unleashed a wave of new players crawling the web, often offering nothing in return. Much like early Google News aggregating snippets (which infuriated publishers), AI companies now repurpose the content they ingest and serve it directly in chat responses or summaries, without sending users to the original source. It’s breaking the ad-based Faustian bargain. Content creators, realizing their work is being pillaged instead of traded, are rapidly fencing off their gardens. Paywalls are rising higher than ever, and anti-bot measures are getting more aggressive. In an ironic twist, human users often get caught in the crossfire of bot hunting Inquisition (CAPTCHAs, login walls, broken RSS feeds), as sites desperately try to distinguish real readers from scraping bots. The once-open web is curling back into a fragmented, medieval patchwork of walled cities. Walled cities against the botsEven Google, realizing its core search business is at risk, has decided to commit seppuku rather than be usurped by outsiders. Google is now rolling out AI-generated answers in search results, essentially cannibalizing its own traffic. “Sure, Search might die, but I’d rather kill it myself first.” Like the dolphins in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, they’re waving as they swim away: “So long, and thanks for all the crawled content.”. Early evidence from Google’s experiment is sobering: when Google shows AI answers, organic results suffer a ~50% drop in clicks. In other words, content creators are getting drastically fewer visitors because Google’s AI is answering the query directly, and advertisers, seeing organic reach dry up, have little choice but to pour more money into ads for visibility. Turns out the obituaries were premature: Google ad revenue is up 10%. Meanwhile, Meta has been fighting its own wars. Apple’s App Tracking Transparency (ATT) measures dealt a heavy blow to Meta’s ad targeting in 2022, an estimated %37 decrease on click-through rates. Zuckerberg’s costly bet on the Metaverse didn’t pan out, and the core ad-based model remains under threat. Zuck is now in the arena, waving an American flag while fighting everyone with his Open Source AI strategy. But the Chinese labs are playing the same game, and despite GPU bans, they are taking over the benchmarks. And then there’s Cloudflare, quietly rubbing its hands like an old-school gangster offering protection. “Your content is safe with us,” they say, while simultaneously launching browser automation to those with crawling needs. In July 2025, Cloudflare announced a new service to block AI crawlers by default unless they pay up or get permission. It’s offering a potentially lucrative third way for the Internet’s future. It’s not a classic paywall. It’s not ads. It’s essentially “Pay to Crawl”: think of it as the digital equivalent of a nightclub’s ladies’ night: humans get in free, bots pay cover. Reddit, Stack Overflow, and major news publishers are already striking data licensing deals, turning this data monetization model into reality. In effect, if data is fossil fuel, the web’s knowledge is being fracked at all costs. Lastly, as generative bots overrun the public web, humans are retreating to more intimate corners. The cozy web of private chats, invite-only forums, and niche communities. When every other social post or blog could be written by ChatGPT, people naturally gravitate to spaces where real identity and authenticity are ensured. It’s the chess problem: robots may play perfectly, but nobody shows up to watch robots play each other. This has lead to a resurgence of email newsletters, influencers, small Discord communities, and Substacks where a named human is accountable for the content. robots dominate the open webA Dream of Spring: The Internet to come Eventually, the dust will settle. Some players will win (and take all), others will fall. But a new equilibrium must emerge. One that rebalances the interests of content creators, consumers, and advertisers. I could stop here and call it a day. But if you’ve made it this far, you deserve more than an open‑ended conclusion. The past and present are easy. An LLM can already write them better than I can. The future? That’s exposure. I’ll make the call and own it if I’m wrong. Looking ahead, the collapsing ad-funded, crawl-for-traffic model seems likely to resolve into three intertwined markets: Ad-based Consumer AI: Whether it’s an AI chatbot, personal assistant, or generative search hybrid, the winner of the consumer AI category will become a new Super-Aggregator. They’ll replace search (and perhaps even browsers, which every company seems to be building) as the gateway through which billions access information and services. And they will monetize primarily via advertising. Why ads? Again? Because it’s too much money for anyone to leave on the table. In 2024, Google made ~$265B from ads. To match that with subscriptions alone would be herculean: it’d take roughly 13 billion monthly $20 subscriptions. That’s 5 billion short of Earth’s population, and demographic collapse and virtual waifus won’t save that math. The business logic points toward a free (or low-cost) consumer AI service with a massive user base, monetized by targeted advertising, just as search and social networks were. The Open Cozy web: Trust in faceless content and large media will erode. When any article might be AI-generated slop, people will increasingly trust individuals and communities instead. There will be just too much content to be able to sift the signal from the noise. Influencers, domain experts, and friend networks will become the sources people rely on more than generic brands. We’re already seeing the shift: readers flock to personal Substack newsletters from writers they trust, and niche, closed communities thrive while broad public forums struggle with bot moderation. In this future, human provenance is the key problem to solve. We’ll need individual “fingerprints” to verify that specific humans created specific pieces of content. Once we can reliably prove and label human‑made work, I’m optimistic that the pendulum will swing back from centralized, walled platforms to a constellation of decentralized, open spaces. Pay for Crawl: Quality human-generated data will become scarce and more valuable, especially as the Internet’s data gets increasingly contaminated by AI output. Models are already being trained on AI-generated content, and like royal inbreeding, the results aren’t looking good. Pay‑per‑Crawl will displace content‑licensing. Licensing builds walls: everything behind a fence, more logins, more friction, less traffic. Pay‑per‑Crawl strikes the perfect balance: humans can roam freely, but bots pay at the gate. Perhaps browsers will carry a kind of “human token” to prove you’re not a bot (a modern twist on HTCPCP). The open web won’t die, but it’s likely to have ID checks at the gate. robots showing ID at the gateWho will be the consumer AI winner? Two frontrunners stand out to me, for very different reasons: OpenAI: They currently have the strongest consumer AI brand. Despite the clunky name, “ChatGPT” has become synonymous with AI for hundreds of millions of people. OpenAI’s move to integrate web browsing into ChatGPT (with source citations and clickable results) is a clever attempt to repair relations with content creators by sending traffic back. But to truly reach Google-like gargantuan revenues, they would need to introduce advertising or sponsored results. OpenAI’s partnership with Microsoft (which brings Bing’s search index and advertising platform into the mix) hints that ads could be coming. If OpenAI can leverage its head start in user base, but it faces the challenge of scaling revenues without alienating users: not everyone will tolerate ads in their assistant. Google: Don’t leave out the current king. Google has decades of experience integrating ads in a way users tolerate, and it already has relationships with millions of advertisers. It also still controls Android, Chrome, Gmail, Maps, YouTube, and other personal platforms that give it a ridiculous data and distribution advantage. While Google was caught unprepared by the launch of ChatGPT, by 2025 it launched capable large models of its own (Gemini, Imagen, Veo, etc.), demonstrating serious technical muscle. Critically, Google doesn’t have to justify a sky-high startup valuation: it’s immensely profitable already and can afford to play the long game. This might allow Google to adopt AI more deliberately, balancing the interests of advertisers, content creators and consumers as it transitions. In the end, Google’s biggest advantage is that it controls the default channels (your phone, your browser, your email) and can bake its AI into all of the above. That, combined with a less constrained business model (they won’t mind cannibalizing some revenue to protect their moat), makes Google a formidable contender in the consumer AI game. My bet is on Google pulling through. That’s it, I said it. So, the bargain that ruled the Internet for two decades is ending. The free ride of free content, propped up by unseen ad targeting, is giving way to something new, something perhaps more balanced, but also more fragmented. “Software is eating the world,” Marc Andreessen declared in 2011. Now, “AI is eating the Internet”. The only questions are: who gets to digest the value, and how will the meal be shared? What do you think? What’s your take? The winter winds are howling, but perhaps, just perhaps, a new spring is coming.

- ai

- essay

- +3

-

Ruthless prioritization while the dog pees on the floor

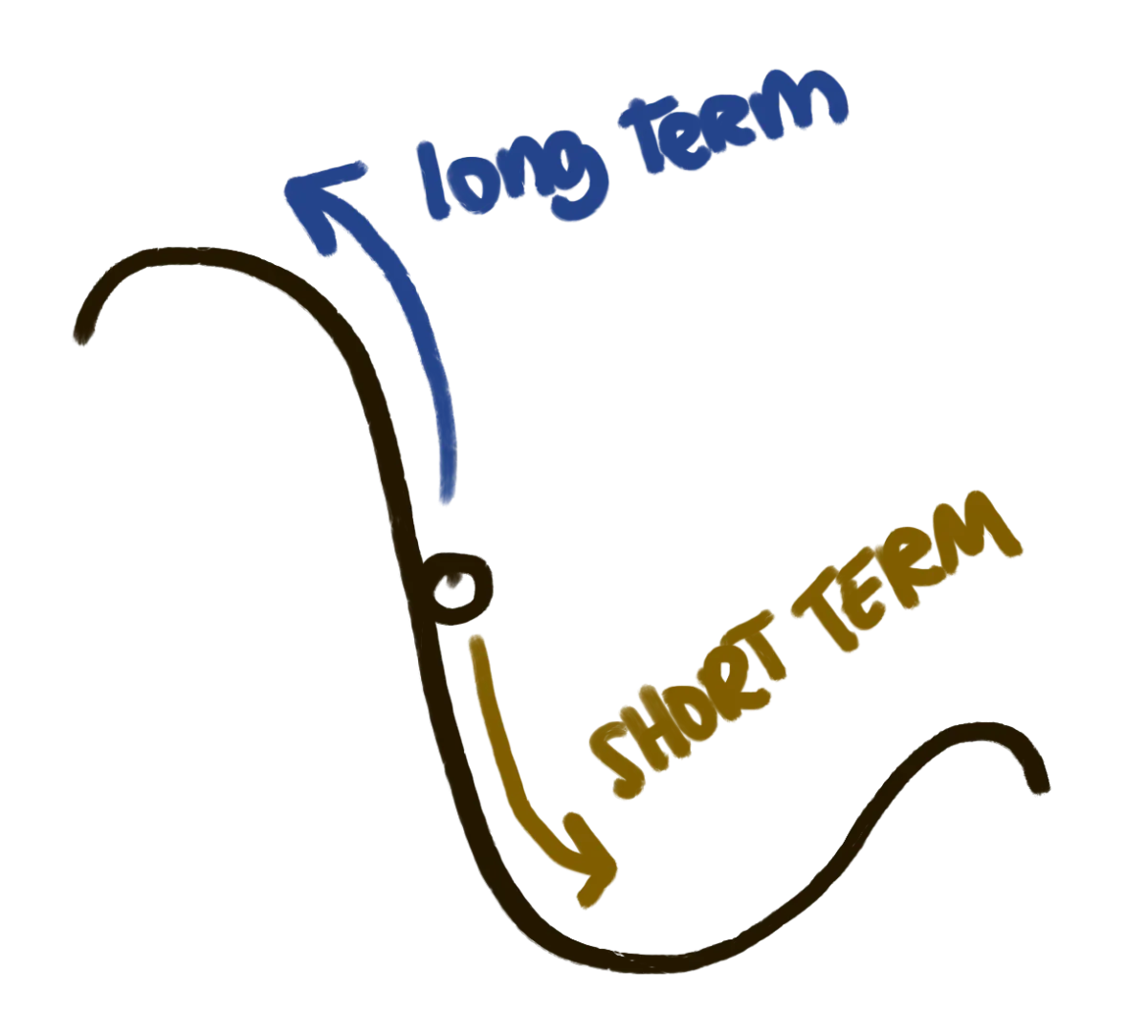

Jun 30 ⎯ Great article on prioritization, and the friction that generates when people don’t understand the most important tenet of prioritization: Time is a zero-sum resource: An hour spent on one thing necessarily means not spending an hour on the entire universe of alternative things There are always more things to be done than time to do them. Hence, in order to do The Most Important Thing, we need to say no to everything else (or at least, not yet). There will always people on the organization that will disagree, and in my opinion, the biggest divide is about time horizons. Some people work with shorter time horizons: they are just more aware than not being alive next month is more important than not being alive next year, and an accumulation of failed strategic initiatives have made more cynical. This pisses off long term thinkers. Which feel trapped in a local minimum and feel the organization is constantly chasing opportunities and not being strategic. So, the problem with ruthless prioritization is that no one really knows where that 10x level is. Short term and long term thinkers have different risk profiles and will chase different directions. Great companies do both. Willingly or accidentally, they allocate most resources to short term initiatives, while leaving some percentage to chase long shots. I think this is another form of slack, which is what allows complex organisms to find global maxima.

-

Building a web game in 2025

May 29 ⎯ This is my series of blog posts describing how I built my game, Whatajong. It’s March 2010 and everyone you know is playing FarmVille. You’re a little ashamed to admit it, but you also enjoy playing from time to time. FarmVille is a Flash game that has gone viral on Facebook, and Zynga, the studio behind it, is on the verge of going public. At that time, there were around 2 billion users on the internet, and 80 million were monthly active FarmVille players. Facebook was just one of many sites hosting Flash games, if you count others like Newsgrounds, I wouldn’t be surprised if the total had reached 100 million monthly players. That was 5% of all the internet users. Wild! But I doubt we’ll ever see anything like it again: it was the peak of casual gaming in the browser. One month later, Steve Jobs published an open letter called “Thoughts on Flash”, effectively dooming the web as a platform for game distribution. The iPhone took over the world and smart phones became the dominant gaming platform. Flash was dead, and HTML5 wasn’t ready, but more importantly, mobile changed the distribution model for games. If you were a developer looking to reach an audience, your best shot was getting into an app store. And speaking of stores, Steam was about to explode in popularity, porting the store model to the PC too. Fifteen years later, driven by a bit of nostalgia, I wanted to explore whether the web could be a viable platform for games again. Here’s what I found: The good The good news is that you can build pretty much anything. The web has now more APIs than Flash ever did. To me, the biggest upsides are: Distribution: The web is unbeatable here. I send you a link, and you can play my game. No downloads, no installations, no stores required. Cross-platform: Porting games across platforms is one of the biggest headaches. The web, despite its historical quirks, is pretty good at this. And with Electron and Capacitorjs it’s easier than ever to create builds for any store. But wait… why would you want to do that? Wasn’t the web the ultimate distribution platform? I’ll revisit that, because it’s not so simple. Layouts: Game UI is one of the least fun and most underappreciated parts of development. Making layouts responsive to different screen sizes can be a huge time sink. But the web has great layout primitives, specially with grid layouts. You can define your UI as a set of constraints and let the browser take care of the rest. DX: Tooling is pretty good. With tools like Vite, you get instant hot reload and fast build times. The browser’s inspector and debugger are solid and you can use Typescript, which is a pretty good typed language that can speed up a lot development. I know, I know. It’s not C#, but it’s not GDScript either. SVG: Vector graphics are lightweight, scalable, and easy to morph. Flash started as a tool for animating vectors, after all. SVG can do much more than most people realize. You can animate with CSS or SMIL, and filters (your “poor man’s shaders”) let you pull off some really amazing stuff. The bad Now for the rough edges, things that’ll make you question choosing the web as your game-development platform. A lot of these issues stem from the web’s greatest strength and weakness: high-level APIs that abstract complexity but limit access to low-level control. Performance: It’s gotten better, but performance is still a concern for certain types of games. JavaScript isn’t the fastest language, and more importantly, it’s single-threaded. You need to be clever to avoid jank. That usually means leveraging Web APIs to offload as much work as possible to the GPU (WebGL, and eventually WebGPU). A lot of animations can run on the GPU, but more on that below. Animations: I was pleasantly surprised by how smooth and easy animations are. You can get 90% of what you want without much optimization. But for the remaining 10%… it’s just either not possible or a pain to work around. Thankfully, browser dev tools offer great insight into why your animation might be dropping frames. I stuck with plain CSS, no Motion, no GSAP, not even Web Animation API, and it handled all my needs. Sound & Music: For some reason, I just couldn’t get sounds to be as snappy as I wanted. That’s frustrating, especially for certain actions that need instant feedback. Also, because autoplay is forbidden on the web, users have to interact with the page to unlock audio. I also had some issues with Safari, but Howler helps by smoothing out cross-browser quirks. Combine it with audiosprite, and you can juggle multiple tracks and transitions fairly easily. The ugly These aren’t deal-breakers, and they’re not outright bad either. Just how things are in 2025. Ugly. Ecosystem: You can’t talk platforms without talking ecosystems. A platform is not just a bunch of APIs and tools, but everything around it too: tutorials, articles, third-party plugins, integrations, community, etc... And the reality is that in 2025, there is a platform that is overwhelmingly dominant, and that’s Unity. Sure, Balatro was built in LÖVE, and Animal Well was famously rawdogged in C++, but you can’t ignore the sheer gravity of Unity’s ecosystem. Distribution (again): I leave this one for the last one, because for me, it was the bitterest lesson: Game distribution is ruled by Aggregation Theory. Consoles: My game was mostly targeting mobile and PC, since that’s were my target audience is. I haven’t explored consoles at all but my guess is that porting to different consoles is harder or impossible for web-based games. App Stores and Aggregation Theory One of the internet’s core lessons is that whoever aggregates demand controls the supply. This can be either by virtue of user experience (you prefer buying on amazon) or channel control (you don’t have a choice on iPhone). Ben Thompson from Stratechery called this framework Aggregation Theory: [...] First, the Internet has made distribution (of digital goods) free, neutralizing the advantage that pre-Internet distributors leveraged to integrate with suppliers. Secondly, the Internet has made transaction costs zero, making it viable for a distributor to integrate forward with end users/consumers at scale. This has fundamentally changed the plane of competition: no longer do distributors compete based upon exclusive supplier relationships, with consumers/users an afterthought. Instead, suppliers can be commoditized leaving consumers/users as a first order priority. By extension, this means that the most important factor determining success is the user experience: the best distributors/aggregators/market-makers win by providing the best experience, which earns them the most consumers/users, which attracts the most suppliers, which enhances the user experience in a virtuous cycle. […] How does this apply to games? Demand is fully aggregated on every major platform. Want to sell a game? Good luck avoiding the stores. Steam rules PC, and the App Store and Play Store dominate mobile. Players simply don’t buy games elsewhere. Sure, there is itch, but expect niche traffic at best. […see edit below] Final Thoughts Whether or not to build on the web really depends on your game’s complexity. For a casual or mini game, the web is likely the better option. You’ll move faster and be more productive. But for complex games needing low-level access, you’ll waste too much time fighting the platform. I’m glad I explored the web as a platform for my casual game. It’s a viable option, and I wish more people took it seriously. But unless you already have an audience or stumble upon a novel distribution channel, don’t get your hopes up. This isn’t 2010, and no one plays FarmVille anymore. Edit: After publishing this article, a few people pointed out that I missed some of the biggest players: Poki (90M MAU), Crazy Games (30M MAU), Minclip (400M MAU) and Y8. (30M MAU). That’s a massive audience. With 5.6 billion internet users, nearly 10% are playing on these platforms. Maybe I was too quick to dismiss the web as a viable distribution channel. In comparison, Steam has 120M MAU. This is exactly why I write: to share what I’ve learned, and to learn from those who read it.

-

How to build a game without spending thousands of euros and hours.

May 15 ⎯ This is my series of blog posts describing how I built my game Whatajong. It’s Monday, and my nipples are hard. I’m not aroused, is just cold in February. I open my laptop and a strange screen greets me: “Access denied: This computer is the property of FleibaCorp”. I no longer work there and now my computer is bricked. Perfect. An excuse to start a side-project from my side-project. “I will build a game,” I tell myself. “Last time I did, it was awesome.” But boy, did the world change since then! Games are both easier and harder to build. On one hand, we have better tools, more tutorials, free assets and AI. On the other hand, every hour a new game is released by a 30-something industry veteran who just spent the last four years isolated in a Wisconsin barn writing their own game engine in C++, drawing thousands of gorgeous assets by hand, and composing music with handmade synthesizers. So before writing a single line of code, I set my constraints: I won’t spend any money. I won’t invest more than 200 hours. Make something fun that sells at least 200 copies. But then, how does one build something relevant in such a competitive market? After much thought, my conclusion is that one must leverage emergence, or said otherwise, complexity that arises from simple things. Designing a game at the edge of chaos Some of the most enduring games have extremely simple rules yet are endlessly deep. Take Go, for example. You can learn it in two minutes but spend a lifetime mastering it. This is because the rules of Go are emergent, a quality it shares with life, and computation. One of the best ways to understand emergence is through the work of Stephen Wolfram on Cellular Automata. He created 256 tiny programs, each with just 8 rules and a 3-bit input, and observed how they behaved over time. He categorized their behavior into four classes: Class I: Evolves to a uniform, stable state (order). Class II: Evolves into simple, repetitive patterns (periodicity). Class III: Evolves into chaotic, random-looking behavior (chaos). Class IV: Produces complex, localized structures that interact. This is where emergence happens. Class IV systems sit right at the edge of chaos. Nudge them slightly, and they tip into order or into disorder. It’s the Goldilocks zone where computation, life, and, yes, interesting games emerge. So why is the edge of chaos so special? And what does it have to do with game design Well, let’s first understand what makes a game fun. What Makes a Game Fun? Games engage the player by presenting meaningful decisions. It's the designer's job to create tensions within those decisions that feel rewarding to resolve. “Should I move the Queen now? If I do, my opponent might pressure me and gain tempo. But if I don’t, I might lose control of the center.” Good games reward good decisions. But in order to make those decisions, the player must be able to predict the outcome. If the future is too predictable, the game becomes boring. If it’s too random, the player feels helpless. Just like with Cellular Automata, fun lies in the middle, in that sweet spot between order and chaos. Let’s consider four games and see how they relate to this spectrum: Class I – Tic-tac-toe: Quickly collapses into predictable patterns. No depth after basic mastery. Class II – Checkers: Offers more variation but still cycles through common, repetitive structures. Class III – Snakes and Ladders: Pure randomness. No meaningful decisions, no agency. CLASS IV – Chess: Balances structure and flexibility. Strategic openings, evolving mid-games, and complex endgames. Chess isn’t Turing-complete, but it’s close. It’s a textbook Class IV system: structured, unpredictable, and full of emergent depth. Related reading: Planning - The Core Reason Why Gameplay Feels Good. How did I apply this learning at my game? When designing a game, I like to start with the core decisions I want the player to make. In Whatajong, the key decision is: “In what order should I clear the board?” To make that decision compelling, I built in multiple layers of tension: Hidden pieces: Some tiles are hidden, so players can't plan with perfect information. They must account for uncertainty. Repeated tiles: Having repeated tiles creates a tension since there are 2 ways you can pair them. You need to develop heuristics to understand which tiles to clear first. Points & Time: Players must reach a point goal, encouraging optimization. But there's a time penalty, which discourages exhaustive calculations and pushes players toward heuristics. This solves the Balatro Cursed Design Problem. Winds: Winds push tiles in one direction. Sometimes this has the side effect of placing a tile on top of its pair, making the board unsolvable. I give wind tiles to the player early because they inject just enough chaos to keep the game on the goldilocks zone. Dragons and Colors: This mechanic drives the scoring engine. Players are rewarded for clearing tiles of a specific color, but sometimes does tiles are not available. This forces players to make decisions on what colors to engage with, and which to sacrifice. Money allocation: Money spent on one item, is not spent elsewhere. Since you don’t know what the next re-roll or round will give you, you must take decisions based on the limited knowledge you have. It also presents long-term decisions such as what build to pursue to be able to pass the future levels. Conclusion If you are building a game, and you are tight on resources (money & time), it’s a good idea to look for emergence. Look for a small set of rules that generate complex decisions. Aim for the edge of chaos: not too random, not too rigid. This approach will save you countless hours of content creation, asset design, and level building. Just focus on the tensions you want the player to feel, and use the minimum rules required to create them.

-

It's Balatro but instead of poker is XXX

May 15 ⎯ This is my series of blog posts describing how I built my game, Whatajong. To build my game, I started by re-writing the old code from a game I built 12 years ago during the golden age of Flash and Facebook games: A Mahjong Solitaire called Whatajong. Though the original Whatajong was, in my opinion, ahead of its time, most critics hated it. Still, a small circle of friends waster hundreds of hours into it, and for me, that felt far more meaningful than positive reviews. I think is worth sharing one of the more memorable reviews it received: “Whatajong will not surprise you with anything. At least nothing pleasant […] The visuals are primitive, but clear and quite pleasant. What will probably drive you to the brink of madness very quickly, however, are the sounds. The demented grin that sounds when you fail to clear the playing field makes the player want to hit the monitor. [...] As a result, there is basically no reason to play this game when there are a whole range of competitors with whom spending time is simply more pleasant.” Finding the game After about twenty hours of tinkering with a new prototype, I showed it to a group of colleagues. Ray, one of the most optimistic people I know, leaned forward and said, “Hey, Pao. The game looks very promising, but you know what would be even better? A Balatro version of this game. Balatro sold like a zillion copies, and clones are popping left and right.” I’m not much of a gamer myself, but I can identify hard drugs when I see them. Balatro looks like heroin to me, so if I wanted to adapt my game to be a Balatro-like, I would have to base my whole research by just watching videos and reading articles. Balatro is misleading because the game is not about building poker hands, but to build tiny “programs” made of Joker cards. The poker hands are just an input for the computation: Like cellular automata, each Joker contains very simple rules, but when combined properly, they produce emergent behaviour that translates into numbers going up. Wisdom nugget #1 – “People love numbers going up.” Jokers are a game-design masterclass and Local Thunk’s Guidelines for joker design is a must read for anyone trying to build games. It’s like Balatro but instead of poker is Mahjong… I spent a week porting Balatro’s mechanics into my game. The fit was surprisingly natural, and I managed to translate most of the concepts I wanted to bring over. I then used Midjourney to generate a hundred Joker art concepts while brainstorming rules to produce that emergent complexity I was after. Joker cards for my whatajong gameEverything seemed to be going smoothly, but at some point I had to address the elephant in the room. Who is this game for? I knew the answer, since it was not the first time I built this game: a middle-aged/senior person who plays solitaire games at work, toilette, or both. When I adapted the prototype for mobile, I found that the most successful Mahjong apps (10 million+ downloads) all feature large tiles and full-screen layouts. That left almost no room for my Jokers. some of the most popular mahjong games in the play storeTo make things worse, early players seem very confused about the Jokers. They never bought them, and while playing, didn’t notice that they even existed. Perhaps it was just a UI problem, but I think the game is just fundamentally too different and I was trying to paint stripes on an elephant and call it a zebra. The problem is that the core mechanic of Mahjong solitaire isn’t as light and instantaneous as Balatro’s. Mahjong is a deliberate puzzle that demands time and full mental focus. In Balatro, both the poker hand and the shop feel like slot machines, which is exactly what makes it so addictive. It became clear that I had to rethink my game from the ground up: emergent gameplay needed to take place on the board itself, not hidden in the deck-building. The shop, therefore, would have to become simpler, like a satisfying reward earned after a mental workout. I ripped out the Jokers and introduced their most interesting rules into new tile types. I rebuilt the progression system around a simple draft shop inspired by Hearthstone Battlegrounds: you choose from a rotating pool of tiles each round; buying three of the same type upgrades them, and if you run out of coins, you can freeze options for next time. That’s it. I let my seven-year-old try the new version of the game, and he absolutely loved it. From that moment on, he asked me every day to play and quickly became my favorite design partner. Whenever I tell him it’s time to stop, he pleads to wait just until he reaches the shop. He enjoys upgrading his tiles even more than clearing the board. Wisdom nugget #2 – “People love evolving things.” Final thoughts Ultimately, drawing inspiration from other games can be a powerful way to get started. It’s well known that combining existing ideas is one of the most effective routes of creativity. For instance, a handy exercise when you’re stuck is to write down random concepts on slips of paper, toss them into a bag, and then draw a few at random, forcing unexpected connections that spark new ideas. “An italian plumber, mushrooms, turtles and a princess? Fine, challenge accepted.” The same principle applies to game design. Crafting “the X for Y” is a perfectly valid approach, but you must deeply understand the design constraints of both X and Y, and who you’re designing for. Without that insight, you will probably end up with a game that is just not fun.

-

A steam locomotive from 1993 broke my yarn test

Apr 03 ⎯ This is one of the few precious articles where an outstanding title lives up to the expectations. I love the “spelunking weird errors” genre, and this one is excellent.

-

Garner and the category making business

Feb 08 ⎯ During my time as CTO of Redbooth, we somehow (paying money) ended up in the magic cuadrant of “unified communications”. Our CEO thought that this would do anything to our sales, but of course it didn't: Our customers where small businesses and marketing agencies, not executives that read Gartner’s bullshit to make IT decisions. That cuadrant meant changing the roadmap to shoehorn “unified communications” features, ceiling the product and eventually having to merge with another company. And for what? Have you heard of that term in the last 10 years? No. It faded away, like all those inventions that are made up to justify Gartner's business model. This is not how companies but software anymore. IT doesn't but software like they use to. With the arrival of the iPhone, employees have revolted and bring their own software to work. I don't short, but if I did, I would definitely short Gartner.

-

Why aren't you idempotent?

Feb 07 ⎯ Very good review about some techniques to achieve idempotency. One interesting insight is the performance implications of idempotency. It is quite known that an idempotent action is more resilient, since it can be retired safely, but the article goes beyond explaining how can it also improve latency by hedging requests: Per Jeff Dean in The Tail at Scale, one of the most effective ways to curb latency variability is to hedge your requests, which means to send it to many replicas. This is very similar to retrying on a timeout (or other error), except you're being more proactive and typically hedge after a delay much shorter than your configured timeout. Hedging comes with the same precondition of idempotency as many replicas could be processing the request in parallel.

-

New solution to the list labeling problem

Feb 07 ⎯ Imagine, for example, that you keep your books clumped together, leaving empty space on the far right of the shelf. Then, if you add a book by Isabel Allende to your collection, you might have to move every book on the shelf to make room for it. That would be a time-consuming operation. And if you then get a book by Douglas Adams, you’ll have to do it all over again. A better arrangement would leave unoccupied spaces distributed throughout the shelf — but how, exactly, should they be distributed?

-

Ideas vs execution

Feb 07 ⎯ Another exploration of what AI means to software engineering. It's always interesting to see how things change when costs trend down. Programming use to be very expensive, but now is becoming commodotized. Ya know that old saying ideas are cheap and execution is everything? Well it's being flipped on it's head by AI. Execution is now cheap. All that matters now is brand, distribution, ideas and retaining people who get it. The entire concept of time and delivery pace is different now. - Geoffrey Huntley

-

On preventing mistakes

Feb 03 ⎯ The culture of postmortems makes us overreact on not repeating mistakes. But perhaps, we should be more categorical about preventing new ones. I often think that a better rule of thumb to postmortems could be: If it’s the first time a mistake happens, acknowledge it and move on. If it’s the second time, then ensure that it does not happen again. This would save organizations from a lot of useless policies and initiatives, since most mistakes only happen once.

-

The only AI for me are the mad ones... Awww!

Jan 31 ⎯ A take on how docile and boring AI gets as an intellectual companion. The article reviews several episodes of people getting mad⎯including Gandalf, and how genuine those interactions feel instead of AI’s servant-style. This reminds me of Jack Kerouac’s most famous quote from “On the road”. What will it take to have an AI to behave like Neal Cassady*? …the only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars and in the middle you see the blue centerlight pop and everybody goes “Awww! ⎯ Jack Kerouac (*) or Dean Moriarty, depending on which version you’ve read

-

On fixing things

Jan 30 ⎯ Seneca pointed out that people tend to be reflexively stingy with their money, but almost comically wasteful with their time. There are at least two ways to take this. One is that Seneca thought he used his time better than you and I do, and maybe he did. Another interpretation is that everyday life, for most people, is an untapped gold mine. Things break all the time, and we get used to it. We accept a decreased quality of life when most things just require a little time investment to be fixed. This article is a short and sweet reminder to invest your time in fixing stuff. A message that resonates a lot with developers, which spend most of their time fighting brokenness.

-

DBs vs sheets

Jan 30 ⎯ Yet another exploration of bridging the mother of all software (excel) with databases. I'm curious to see the UX, since there are definitely challenges to trying to square the circle. It is true that Postgres, with RLS, can get closer to an excel experience, since authorization is one of the biggest gaps to overcome.

-

Ockham's razor is losing it's edge

Jan 29 ⎯ Very interesting study that explore what we've been preaching for a long time: nature is complex, and so ought to be the models that explain it. Medieval friar William of Ockham posited a famous idea: always pick the simplest explanation. Often referred to as the parsimony principle, “Ockham’s razor” has shaped scientific decisions for centuries. Humans are obsessed with simplicity. After all, there is beauty in compressing. But also, our brains are rather limited, so we overindex legible models over illegible ones. But with AI taking over science, this limitation may be gone.